'We can certainly make people sick':

Edmonton restaurant workers

sound alarm on food safety risks

"Are there not enough inspectors? Is it a budget situation? Because playing around with health and safety is a dangerous, dangerous game”

Mice, cockroaches, unwashed hands, and serving expired food.

As part of a six-month investigation by the Edmonton Journal and MacEwan University’s journalism program, scores of local restaurant workers are revealing stomach-churning conditions in their kitchens. Many described shocking violations that occurred during large gaps between health and safety inspections — and when few staff are required to complete basic food safety training

“We’re told it’s a financial issue to improve health and safety,” said one worker, who spent five years working as a bartender and server at a city restaurant.

“I was just thrown in on a busy day with no training,” said another.

A third said a manager became irate when staff used too much bleach and paper towels.

All three were among a total of 65 restaurant workers — ranging from teenagers to those in their late 50s — who spoke to the Journal-MacEwan on the condition of anonymity, many to avoid jeopardizing their employment in the food service industry.

Risky Restaurants

Nearly 20 years after exposing a lack of transparency in Alberta’s restaurant inspection system, the Edmonton Journal has teamed up with MacEwan University for Risky Restaurants. We explore ongoing issues in how food safety standards are enforced, including lengthy gaps between inspector visits, repeat problems on followup, and calls to reform both the inspection system and public access to health information. content

• Day 2: Restaurant workers sound the alarm on food safety risks

• Day 3: Chefs back call for inspection system reform

The most common health violations witnessed by staff were infrequent hand washing and unsanitary equipment.

Restaurant workers also reported seeing spoiled produce, expired food and undercooked food being served to customers. Nearly half reported seeing food left out at unsafe temperatures.

One restaurant worker even recalled when a steak was served after it fell on the floor. Kitchen staff just put it back on the grill before re-plating it.

In addition, some reported efforts by restaurants to learn ahead of time when inspectors were showing up, taking advantage of an inspector workforce that is allegedly stretched too thin. These disturbing disclosures from industry insiders come after the Journal-MacEwan investigation revealed that hundreds of restaurants had not been inspected in the past two years, establishments were allowed to remain open despite ongoing cockroach infestations, and over 2,000 Edmonton food establishments had at least one “critical” food safety violation in 2024.

Further, the investigation found that 77 per cent of food establishments inspected over a 38-month period were not in compliance with food safety regulations, with a whopping 39 per cent recurrence rate.

Alberta Health Services (AHS) said provincial authorities continually review inspection practices, policies and enforcement tools, and that additional options are under consideration to better address repeated non-compliance.

“Repeat violations may occur for various reasons, including staff turnover, which is why regular monitoring is essential,” a statement from AHS reads.

“While operators are responsible for complying with the Public Health Act and its regulations, balancing support and accountability helps ensure they understand their legal duties and the risks of non-compliance.”

‘Who is dropping the ball here?’

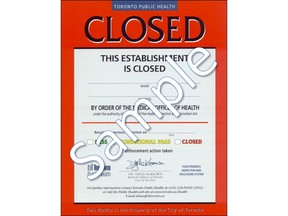

Restaurant staff and customers who spoke with the Journal-MacEwan are strongly backing calls to overhaul Alberta’s restaurant inspection system by implementing key features of the DineSafe program.

The award-winning program, which uses colour-coded safety ratings for restaurants, combined with stricter enforcement, is seen as the gold standard in food safety. It was credited with a 30 per cent drop in foodborne illness in Toronto after it was implemented in that city.

John Filion, who launched DineSafe as chair of Toronto’s board of health, said the majority of restaurants run a clean kitchen, but bad operators only cleaned up their act in Toronto when they realized they could no longer get away with it under the new program.

It was the fear of being exposed publicly and losing their business, rather than getting a small fine from the health inspector, that caused them to change their behaviour,” he said.

Celebrated food writer Twyla Campbell, who has dined at thousands of restaurants as a reviewer, said tougher enforcement is badly needed to protect customers.

“Who is dropping the ball here?” she said. “Are there not enough inspectors? Is it a budget situation? Because playing around with health and safety is a dangerous, dangerous game.”

No mandatory safety training

One related issue is a lack of training.

In Alberta, all staff who serve alcohol must complete ProServe, a mandatory government course on responsible service to help reduce alcohol-related harm.

Yet there is no requirement for restaurant staff to take basic food handler training on hygiene, saInstead, Alberta requires that only one staff member hold a food safety certificate.

For smaller food establishments, with five or fewer staff, this one person must have “care and control” of the establishment. For larger businesses, only one person on duty needs to be trained.

This is in stark contrast to cities like Los Angeles, which require all staff who prepare, handle or store food to have a valid food handler card.

Marco Ung, a former chef from Los Angeles who recently visited Edmonton, said he was surprised to discover there was no mandatory training on sanitation and hygiene for local servers, bussers, and even cooks.In California, the food handler card is obtained after completing an online safety course, and it’s valid for three years, he said. In Alberta, the province offers a basic training course, in-person, for $125, while private providers offer authorized online courses for as low as $25, which take about six hours to complete.

But some restaurant staff who spoke with the Journal-MacEwan said their food safety training was limited or never occurred. About a third said they were not comfortable with the amount of training they received, and that they often had to pay for courses out of pocket.

“In the first restaurant I worked at, I never really got food safety training. They just kind of threw me in the kitchen,” said one cook.

A restaurant manager revealed they weren’t required to have food handler certification, even after they were promoted: “I had to learn it myself.”

Pamela Apsassin isn’t surprised. After 25 years in the food service industry, working in jobs ranging from dishwasher to kitchen supervisor, she’s seen first-hand how food safety standards are slipping.

“He openly said that he didn’t know anything about sanitary procedures,” she recalled.

Nick Young, a 20-year veteran of the food service industry, blamed the current conditions on the pandemic, when older, more experienced chefs left the industry and never returned.

Restaurants are now operating with significantly reduced staff and fewer “Red Seal” cooks who have completed extensive training and passed a national certification exam, said Young, who asked to use a pseudonym in order to speak publicly about the industry.

Young estimated there has been a 20-25 per cent drop in staffing while restaurants are still trying to maintain or grow their business.

‘We’re dealing with things that can kill people’

Paul Campbell, program chair of NAIT’s department of culinary arts and professional food studies, said food handler safety certification should be expanded, making it mandatory for all restaurant staff.

“It would be a fantastic idea,” said Campbell, who has 14 years of experience as an executive chef, the top job in a restaurant, overseeing everything in a kitchen.

“We’re dealing with things that can kill people,” he said. “We can certainly make people sick.”

Food service industry group Restaurants Canada is not opposed to expanding food safety training for full-time kitchen staff, said western region vice-president Mark von Schellwitz, but he questioned if it would be too burdensome to include part-time staff in such efforts.

Research has shown that mandatory food handler certification is one way to limit the spread of foodborne illnesses.

A 2009 study from the University of Guelph compared food establishments with mandatory food handler certification to those without any certified food handlers. The research found that establishments requiring certification were nearly twice as likely to avoid infractions during inspections.

Similarly, a 2008 study of more than 4,000 restaurants, published in the Journal of Food Protection, found that restaurants with certified kitchen managers were overall less likely to record food safety infractions.

Jim Chan, a retired health inspector from Toronto, said enforcement of the food safety handler requirement is a crucial but often neglected part of restaurant inspections.

“If the inspector is not enforcing that, it’s just a piece of paper stuck to the wall.”

Inspections not always a surprise

In 2003, a University of Alberta study found health authorities needed to allocate more resources to food establishments, such as increased food handler education and increased inspection frequency.

Chan, who helped launch Ontario’s DineSafe program, said he was surprised to see how long Alberta restaurants can go between inspections.

In Ontario, high-risk establishments, such as hospitals and restaurants that serve fresh meat, poultry and seafood, are required to be inspected at least three times a year. Moderate-risk establishments, such as fast-food outlets, are inspected twice a year. Even low-risk food establishments, which serve only pre-packaged foods, are inspected annually, Chan said.

Alberta has a non-mandatory “target” of visiting higher-risk places every 12 months — and is not even meeting that standard.

Indeed, AHS data over a 38-month period, from 2022 to early 2025, revealed that 266 food establishments’ last inspection date was 2022, and another 782 establishments last had an inspection in 2023. The data does not clarify if these establishments are no longer operational or fell through the cracks in AHS’s post-COVID inspection ramp-up.

Even when health inspectors do show up, it is never truly a surprise, said Anthony Sinclair, a long-time restaurant worker in EdmontonThus, inspectors are not getting an accurate picture of what is regularly happening inside the kitchen, he said.

Along Whyte Avenue, restaurant staff at multiple businesses have also started using a WhatsApp group chat to alert each other when inspectors are in the area, according to two sources familiar with the practice, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Similar practices were reported at Red Deer restaurants with staff using a private Facebook group, another source said.

But Restaurants Canada disputes those allegations, said Schellwitz.

“What restaurants want to avoid is having inspectors disrupting operations coming in when restaurants are in their busy service hours,” he said. “Most restaurants are fully cooperative with inspectors and have developed a positive working relationship with health inspectors to ensure their operations are food safe.”

Sinclair said the current inspection process contributes to a culture in which restaurant staff don’t take safety as seriously as they should, and prevents inspectors from catching establishments stuck in bad habits.

“People become lax,” he said. “They say, ‘It’s fine, it’ll be fine, don’t worry about it,’ and then eventually it just goes more and more downhill.”

One of the most common health violations is cleaning without enough sanitizer to stop the spread of pathogens. According to the AHS inspection records, improper housekeeping, equipment sanitation, dishwashing, and hand sinks are among the top-10 recurring infractions. He said repetitive violations are either because the owner doesn’t want to make changes, or they don’t know how to do it. “Which is, I think, even more concerning.”

While the vast majority of restaurant workers who spoke with the Journal-MacEwan said they were comfortable raising food safety concerns with a manager, a handful mentioned a workplace culture of cost-cutting that had seen cleaning supplies dwindle and concerns brushed aside.

“Sometimes, it’s the managers themselves who are practicing unsafe food practices and get mad if you call them out for it,” said one restaurant staff member.

‘Absolute chaos’ for inspectors

Provincial staff shortages and excessive workload among Alberta’s 280 health inspectors are contributing to a food safety crisis, said Mike Parker, president of the Health Sciences Association of Alberta (HSAA).

Burnout has become a major issue, he said, with inspectors tasked with not only monitoring food safety at thousands of restaurants, but any facility that serves food — from daycares and group homes to food trucks and prisons. 00000“What we have right now is absolute chaos,” he said.The Journal-MacEwan contacted multiple health inspectors, but all of them either declined to comment or did not respond. Some inspectors told the Journal-MacEwan they feared employer and government retaliation if they spoke out.

Parker said provincial government staff who have previously spoken out about working conditions have faced being reprimanded, punished, and terminated.

AHS said public health inspectors are employees of the health authority, not the Government of Alberta directly, adding no inspectors have been reprimanded for raising concerns. Food venue inspections continue to be handled by AHS for now, but will be reorganized under the new ministry of Primary and Preventative Health Services later this year, with the ministry stating it will work to strengthen inspection tools and update policies.

AHS stated that food safety is a shared responsibility, and that it encourages all food service staff to take its free online food safety training program.

“Effective food safety depends on strong leadership — business owners and managers should promote good practices by supporting ongoing staff training and modelling proper food handling.''

Restaurant workers want change

In a prepared statement, Restaurants Canada said it does not support introducing the red, yellow, and green inspection notices in Alberta, as used in Toronto and other cities, because the signs can be misleading and unfairly scare away customers.

But nearly 75 per cent of restaurant workers interviewed by the Journal-MacEwan agreed or strongly agreed that restaurants should be required to post a colour-coded sign in the window, showing the result of the most recent health inspection.

That number jumps to over 83 per cent when asked if health inspection grades should be published next to restaurant listings on food delivery apps and on restaurant websites.

And while Toronto restaurants did have serious concerns with DineSafe when it was launched, they came to support it, according to Jason Cheskes, president of the Toronto board of the Ontario ùùùùùùùùùRestaurant Hotel and Motel Association, in a 2011 letter of support for the program to win a major ùThat remains the case even today, said Tony Elenis, the current ORHMA president, who calls DineSafe a good program that delivers what the public expects

AHS stated food delivery apps are not provincially regulated to display inspection results.

It added that Alberta does not currently require food establishments to post inspection reports online, but that those reports are available on the AHS website, adding that it was reviewing inspection systems and may consider options to improve public access.

“The goal is to promote transparency, help Albertans make informed choices, and support compliance among food establishments.

Rebate program suggested

For Nick Young, two decades of industry experience, mostly at fine dining restaurants, have led the experienced cook to believe that providing smaller incentives for restaurant staff would also help improve food safety.

A provincial or federal rebate program to cover the cost of food handler certification would make a big difference, Young said, since a typical line cook is under 23 and living on a tight budget.

The same goes for restaurant owners and managers, who could use help to meet the standards rather than having to pay out-of-pocket, Young added.

“It comes back to money,” Young said. “A financial incentive to motivate employers to have a safe place to work.

“Take the barriers away, because there doesn’t need to be that many.”

— This is the second of a three-part series examining food safety in Alberta’s restaurants. All of the stories can be found here.

MacEwan University contributors: Chris Allen, Rebekah Brunham, Brooklyn Burns, Steve Lillebuen, Raynesh Ram, and David Slater

With additional reporting by Izzy Crozier, Kaitlyn Evans, Lucy Gordon, Edith Juru, Natan Leong, Lexus Morgan, Liam Newbigging, Ryan Reed, Jackson Scherger, and Evan Watt

Enhance your quoting and sales automation skills with expert-led Salesforce CPQ training. The course covers configuration, pricing, and workflows in detail. Perfect for mastering CPQ end-to-end.

ReplyDelete